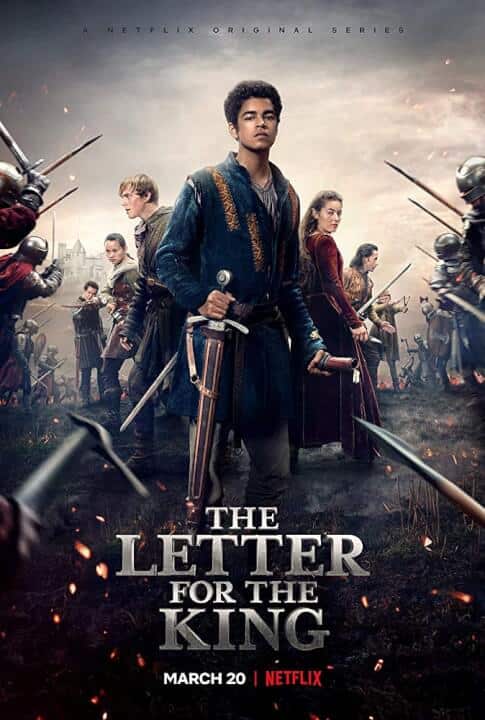

"Pressured by his father and mocked by his peers, 15-year-old Tiuri competes to become a Knight of Dagonaut--just as the kingdom faces a dark threat."

The series description for the Netflix original The Letter for the King sounds promising. As the show gets underway, viewers quickly learn that Tiuri is different from the other novices, displaying both a strong sense of honor and the first stirrings of magic. During the Novices' initiation, Tiuri breaks tradition in order to respond to a desperate call for help beyond the chapel doors. His response leads him to a dying knight, who hands him a letter that must go to the king to prevent Prince Viridian from taking over and unleashing unfathomable darkness upon the world. (For a more in-depth summary, view the Rotten Tomatoes page here; Wikipedia page here)

The first few episodes are riveting. The story's magic system is interesting, featuring a spooky scene in which Prince Viridian roasts a victim over a fire and sucks their magic out of the air. Tiuri hears strange whispers and is told to shut them out. On his journey, he encounters a monastery high in the mountains filled with reformed rogues and murderers in the guise of holy men.

However, by the last few episodes of the eight-episode season, the story falls to pieces and several glaring storytelling problems leap to the forefront. The problems exist throughout the story, but they stand out most in the final episode, especially the final showdown. Throughout the story, viewers have been pulled along, fascinated, teased, spooked, and primed for a big ending! And...

They don't get it.

Instead, the ending is flat, compelling, and confusing. The writers commit several egregious storytelling errors, chronicled here in no particular order.

1. No sense of stake.

The series description for the Netflix original The Letter for the King sounds promising. As the show gets underway, viewers quickly learn that Tiuri is different from the other novices, displaying both a strong sense of honor and the first stirrings of magic. During the Novices' initiation, Tiuri breaks tradition in order to respond to a desperate call for help beyond the chapel doors. His response leads him to a dying knight, who hands him a letter that must go to the king to prevent Prince Viridian from taking over and unleashing unfathomable darkness upon the world. (For a more in-depth summary, view the Rotten Tomatoes page here; Wikipedia page here)

The first few episodes are riveting. The story's magic system is interesting, featuring a spooky scene in which Prince Viridian roasts a victim over a fire and sucks their magic out of the air. Tiuri hears strange whispers and is told to shut them out. On his journey, he encounters a monastery high in the mountains filled with reformed rogues and murderers in the guise of holy men.

However, by the last few episodes of the eight-episode season, the story falls to pieces and several glaring storytelling problems leap to the forefront. The problems exist throughout the story, but they stand out most in the final episode, especially the final showdown. Throughout the story, viewers have been pulled along, fascinated, teased, spooked, and primed for a big ending! And...

They don't get it.

Instead, the ending is flat, compelling, and confusing. The writers commit several egregious storytelling errors, chronicled here in no particular order.

1. No sense of stake.

Although the writers spend the entire series reminding viewers that "there's a darkness coming" upon the kingdom, often in very compelling or mysterious ways, they never demonstrate how that "darkness" will affect the characters. As a result, Tiuri's final battle is about as compelling as a montage of his horseback ride across the mountain. Experienced storytellers know that if viewers don't understand what the characters stand to lose, they will not be interested in the story. Viewers of this story are lacking a sense of what is at stake.

2. The protagonist doesn't solve the problem.

*Spoilers ahead

In the second-to-last episode, viewers suddenly learn that all along it was not Tiuri who was developing magic powers--it was his unwilling friend, Lavinia. This is a major complication when the pair squares up against a magically resurrected Prince Viridian--how will Tiuri defeat a magical being and the greatest darkness he has ever faced with no magical powers?

The answer is--he doesn't. As tendrils of darkness envelop him, Tiuri frowns fiercely at his foe, presumably reaching deep inside to access his own power. Then the darkness surrounds him, and he disappears. Instead, it is Lavinia who uses her power to easily defeat Viridian. The focus shifts completely to Lavinia, framing her as the protagonist instead of Tiuri. This quick switch leaves readers feeling cheated, confused, and disappointed, as the character they are supposed to be following simply disappears at the most important part of the story.

3. The final showdown is far too easy.

Despite the buildup and repeated warnings about inconceivable "darkness," leading viewers to expect a terrifying and nearly indestructible threat, the final battle with Prince Viridian lasts only moments. After Tiuri disappears, Lavinia leverages her powers, glowing brightly as Viridian's darkness tries to swallow her. After a brief few moments of this standoff, Prince Viridian self-destructs. And it's over.

Despite the ominous warnings throughout the series (including one from a chained madman who lurks in the shadows of a strange monastery!), Viridian is disintegrated by a little firefly light from a girl who is not even the protagonist. The power Lavinia displays is also never explained, leaving viewers wondering how the defeat happened. Because viewers are not aware of what both sides of the conflict are capable of, the story feels particularly flat in this area. The episode description promised a "daunting test," but the episode delivered a 2-question true/false quiz. Viewers leave the series with as many questions as they came in with, lacking any kind of satisfaction in the ending.

4. Unfulfilled promises.

Early on, the series made several promises that drew readers in. However, most of the storylines and ideas it started to explore fizzled out, leaving viewers disappointed.

Despite the buildup and repeated warnings about inconceivable "darkness," leading viewers to expect a terrifying and nearly indestructible threat, the final battle with Prince Viridian lasts only moments. After Tiuri disappears, Lavinia leverages her powers, glowing brightly as Viridian's darkness tries to swallow her. After a brief few moments of this standoff, Prince Viridian self-destructs. And it's over.

Despite the ominous warnings throughout the series (including one from a chained madman who lurks in the shadows of a strange monastery!), Viridian is disintegrated by a little firefly light from a girl who is not even the protagonist. The power Lavinia displays is also never explained, leaving viewers wondering how the defeat happened. Because viewers are not aware of what both sides of the conflict are capable of, the story feels particularly flat in this area. The episode description promised a "daunting test," but the episode delivered a 2-question true/false quiz. Viewers leave the series with as many questions as they came in with, lacking any kind of satisfaction in the ending.

4. Unfulfilled promises.

Early on, the series made several promises that drew readers in. However, most of the storylines and ideas it started to explore fizzled out, leaving viewers disappointed.

- Tiuri is often described as "the Shaman's son" and hears whispering voices all the time at the beginning of the series. Instead of exploring this angle, the writers let it fizzle out.

- Multiple characters, including the Black Knight's wife, reference a mysterious prophecy that seems to refer to Tiuri. This prophecy disappears after the fifth or sixth episode and is not referenced again.

- Tiuri and Lavinia stumble upon a monastery full of "monks," who are actually reformed rogues, murderers, and thieves, including at least one "brother" chained up in the corridors! This is the most compelling part of the series and creates a strong sense of mystery--then disappears when the episode ends. (Honestly, I just want Netflix to make a miniseries about these people...)

Instead of exploring any of these interesting possibilities, the writers stuck to a milquetoast main character and a disappointing slate of supporting characters. None of the characters changed or developed. Tiuri didn't even change his facial expressions over the course of the show.

|

| Tiuri does not stop making this single face for the entire series. That's about the level of character development we get from him as well. (Image copyright: Netflix. Source) |

In summary, while the show started off well, the storytelling disintegrated by the end. Newsweek predicts that the show will be renewed for a second season, but after the disappointing ending and poor set-up (to all appearances, the villain has been defeated and only one image at the very end hints at the possibility of a return), I will not be tuning in.

Comments

Post a Comment